The Sweep: Redistricting Wars Begin

In closing the first year of this newsletter, I want to thank every single one of you for reading it, for your emails, and for your comments on the website. I write this with each of you in mind, thinking about what new nerdy corner of the campaign world I can shine some light on that you will find interesting. This newsletter has brought me a lot of joy and that is because of you.

I’ll be taking next week off—I’ve got a pile of books that I’m dying to read—but after that, we will dive right into the 2022 Senate map with our freshly minted results from Georgia to show us the way.

Campaign Quick Hits

Special Turnout for a Special Election: More than 1.3 million ballots are already in for the January 5 runoff—an unprecedentedly high number for a special election. Remarkably, more than 36,000 of those are from Georgians who didn’t vote in November. It’s a little hard for me to wrap my head around the voter who didn’t bother to vote for president but has been persuaded to vote for control of the Senate. No doubt some of them were born in November and December 2002. Maybe some thought Georgia was too deep a red to bother in November but now think their vote actually matters. Maybe they were ill or got distracted on Election Day. Or maybe the campaigns turnout operations—provided with nearly unlimited money (and remember that neither presidential campaign truly put the pedal to the metal in Georgia this cycle)—are truly finding ways to motivate very low propensity voters whom they didn’t have the time or resources to reach just a few months ago. But overall, those 1.3 million voters have left some clues: 25 percent fewer mail-in ballots have been received than by this point in the November election, and there’s been close to a 10 percent increase in in-person voting. Perhaps fears over the pandemic are subsiding, but more likely that looks like pretty good news for Republicans.

Missing in Action: Notice something missing in most of the news coverage in Georgia? Polls! As Politico’s Steve Shepard reported, “Since the general election, FiveThirtyEight has tracked 12 polls of both contests, though most of those polls were conducted by firms with mixed or limited track records: Only two of those surveys were conducted by pollsters the site gives better than a ‘B-’ rating.” Special elections are hard to poll in the best conditions—turnout is often (if not always) significantly smaller than a general or even a midterm election, making it that much harder to determine who is a likely voter. Add to the mix that many people take holidays between Christmas and New Year’s Day and it’s even harder to ensure that your respondents are representative of the January 5 electorate.

Hey Big Spender: We’re up to $450 million in ad spending in Georgia. Yep, that’s a lot. In fact, it’s maybe even near the maximum. As Nick Corasaniti at the New York Times determined, in Georgia right now, “In the 5 p.m. to 6 p.m. hour, home to local news broadcasts and a common target for political campaigns, more than 60 percent of all ads were political.” The returns are diminishing, for sure, but with unlimited budgets, there’s not much of an incentive for the campaigns not to gobble up all that air time.

“The stakes are so high and the margins are so tight that even a really inefficient strategy makes sense for people who are trying to control the United States Senate,” Ken Goldstein, a professor of politics at the University of San Francisco, told the Times.

Incumbency Waning: In 2000, according to a group called FairVote, incumbent congressional candidates could count on getting an 8-point advantage just from being an incumbent. They had higher name ID, better access to donors, the ability to send “free” mail to constituents, credit for earmarks for local taxpayer-funded projects, and, of course, an entire office of staff to help constituents with their problems. Fast forward to 2020, and that advantage has all but disappeared. An incumbent congressional candidate this past November enjoyed a measly 1.4-point incumbency advantage. Candidates matter less, party identification matters more.

Flanking from the Left: As mainstream media continues to focus on the probability of a compromise caucus emerging during a Biden administration without unified congressional control, not everyone is singing from the same hymnal. The most progressive campaign groups—Justice Democrats, Our Revolution, and the Sunrise Movement—didn’t flip a single Republican-held seat. But during primaries they did unseat incumbent Democrats who were seen as insufficiently liberal. And that’s what they plan to keep doing in 2022. As proof of concept, they point to the Tea Party. Strategically, I don’t see why they aren’t right: Threatening members from the far left or right is both more efficient—primaries are cheaper to win and have much lower turnout—and more effective for a minority to build a power base within a party as long as they view continued gridlock as better than compromise.

“It wasn’t that the Tea Party won a ton of swing races,” Max Berger, the former director of progressive outreach for Warren’s presidential campaign, told Politico’s Holly Otterbein. “That’s not what made them powerful. They succeeded because they won a lot of Republican districts, and I don’t see why our project would be significantly different.”

Shifting Voter Trends: The bases of both parties are shifting, leaving both sides a little shaky on where they stand heading into 2022. Comparing 2016 to 2020, “Democrats increased their margins by 4.8 percentage points in college towns, 5.9 points in exurban communities and more than two points in suburban areas. But Trump performed better in big cities by two points, in Hispanic centers by 3.5 points and in working class-dominant parts of the country by nearly a point.” But how much of that was Trump-specific voter behavior? Will Democrats maintain that strong of a grip on the suburbs without him on the ballot? Will Republicans keep making gains with the white working class without him?

“We won back the House and the White House in the suburbs, but my sense is we are leasing that support—we don’t own it,” Robby Mook, the manager of Hillary Clinton’s 2016 campaign who led the House Majority PAC this cycle, told Michael Scerer at the Washington Post. “With Trump gone, that lease is up for renewal. If we don’t hold on to our gains in the suburbs or replace it by winning back working-class White voters, we will have a problem.”

State Legislatures Take the Wheel

For those who follow statehouse races, the 2020 election was remarkable–because nothing much changed.

“It looks like 2020 will see the least party control changes on Election Day since at least 1944 when only four chambers changed hands. In the 1926 and 1928 elections, only one chamber changed hands,” wrote Tim Storey and Wendy Underhill at the National Conference of State Legislatures. In fact, the only two chambers to flip were the New Hampshire Senate and House, which Republicans reclaimed after Democrats flipped them in 2018.

Along with their wins in New Hampshire, Republicans also picked up the Montana governorship, which means they gained two new trifectas—states in which a single party controls the governorship and both legislative chambers.

Republicans now have unified governments in 23 states while Democrats control governorships and state legislatures in 15 states. Eleven states continue to have a divided government—Democratic governors with Republican legislatures in eight states, and Republican governors with Democratic legislatures in three. And then there’s Alaska.*

Now that we know where the ball lies, what does it all mean?

First, of course, state legislatures do have enormous power over our lives. The abortion wars are bound to continue in which unified GOP states pass increasingly harsh and/or creative restrictions on abortion which are then litigated for years. Pro-life proponents were disappointed this past term when Chief Justice Roberts upheld Roe and Casey and struck down a Louisiana law that required abortion providers to have admitting privileges at nearby hospitals. With Justice Amy Coney Barrett shifting the balance of the court, however, state legislatures may head into the breach once more to see whether they might find five votes without Roberts.

Second, that’s not why state legislatures are the focus of The Sweep this week. It’s redistricting! As Article I of the U.S. Constitution so unpoetically tells us, “The actual Enumeration shall be made within three years after the first meeting of the Congress of the United States, and within every subsequent term of ten years, in such manner as they shall by law direct.” And so here we are in 2020 about to get the results of our decennial census, which will lead to two major fights.

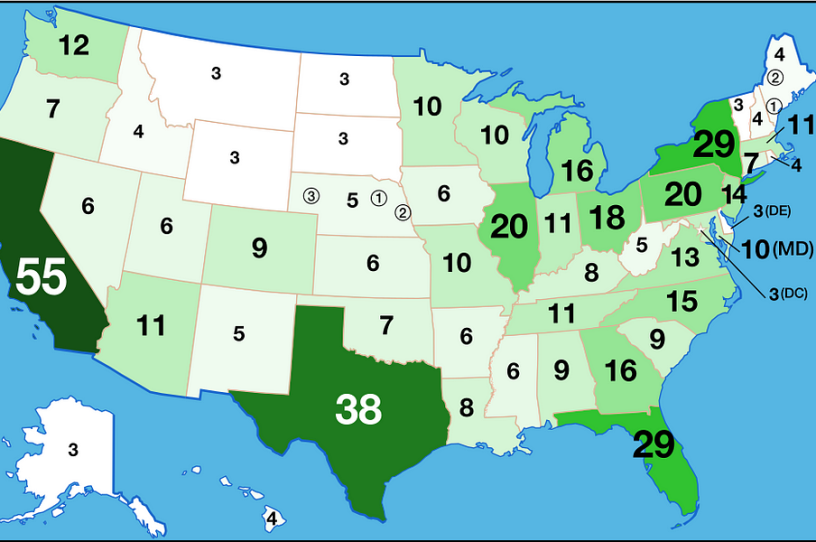

The first fight is over apportionment. That is the question of how many seats each state gets out of the 435 House seats. And it is also worth noting that this apportionment also affects a state’s number of seats in the Electoral College. Nobody seemed to pay much attention to this fight because, well, I don’t really know why. After the 2010 census, for example, Texas picked up four seats, Florida gained two, and Georgia, Nevada, South Carolina, Arizona, Utah, and Washington each got one. On the flip side—this is a zero sum game, after all—Illinois, Iowa, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Michigan, Missouri, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania each lost one seat while New York and Ohio both lost two. Losing seats is a big deal. Poor Iowa lost 20 percent of its representation in the House, going from five seats to four. Ouch!

And this is why apportionment is getting renewed attention this year. President Trump issued a memorandum, “Excluding Illegal Aliens From the Apportionment Base Following the 2020 Census.” In it, he argued that “states adopting policies that encourage illegal aliens to enter this country and that hobble Federal efforts to enforce the immigration laws passed by the Congress should not be rewarded with greater representation in the House of Representatives.” Without naming California, he claimed that “including these illegal aliens in the population of the State for the purpose of apportionment could result in the allocation of two or three more congressional seats than would otherwise be allocated.”

The Supreme Court heard the case earlier this month and ruled that the states would have to wait until they’ve actually been docked seats before suing. Legally, the case is interesting because everyone agrees that the federal government does not count people in the country on tourist visas in the census. But there isn’t agreement on whether the law requires (or simply permits) the government to count someone the day after that visa expires. Politically, it’s not clear whether the secretary of commerce will be able to get the census report to President Trump with enough time before he leaves office or what types of aliens the report will be able to identify. (The Commerce Department has to match up individual census questionnaire respondents with individual records of aliens based on their current detention in an ICE facility, for example, so we know the report cannot and will not include anyone unlawfully present in the country who has never been arrested or given removal orders.)

The second fight—once the apportionment has been completed and the litigation over apportionment resolved—will be over redistricting. And that is why unified party control after 2020 is so important, and why the statehouse races in 2022 may also be important. Except in Montana, Wyoming, the Dakotas, Delaware, Vermont, and Alaska. Can you guess why? They don’t do redistricting because they only have one seat. Womp womp. (Note: Maine has only two, which you’d think would still make it a pretty easy job, but Maine also apportions their Electoral College votes by congressional district—not winner take all like 48 other states—so those lines matter to everyone up and down the ballot.)

Currently, out of the 43 states that may draw new lines every 10 years, more than half involve some sort of redistricting commission at some point in their process. Iowa isn’t one of those states, but it is extra fun because Iowans draw their maps without “any political or election data including the addresses of incumbents.” Some of those states use commissions fully independent of the state legislators, and others, like the one just passed in Virginia in November, are a hybrid of citizens and legislators.

The Supreme Court upheld these commissions in 2015, and in 2019, the justices also held that the courts would not get involved in refereeing partisan gerrymandering either. But that’s not where the legal mess stops. There’s complicated case law around “one person, one vote,” cracking and packing (i.e., intentionally drawing lines to dilute a voting block across districts or concentrate a voting bloc within a single district), and racial gerrymandering. No doubt the subject of a future Advisory Opinions episode.

The point is that these redistricting lawsuits languish for years and across cycles, and the state legislatures are usually stuck in the middle of it—especially in states that lose a seat and incumbent congressional representatives are forced to run against each other or leave office. Of course, that only applies to the shrinking number of state legislatures that do the work themselves.

This isn’t the first time state legislatures have wanted to get rid of their own political power, though. Before 1913, they were in charge of picking their U.S. senators too.

*Alaska was sort of technically a Republican trifecta state heading into 2020, but several members of the Republican legislature broke off and caucused with the Democrats, creating a ‘coalition of the willing’ of sorts for our northern brethren. Because of that, it was counted as one of the 12 divided government states. But as of now, the results of the 2020 election are still too close to call. When it is called, that will mean there are either 24 Republican trifecta states or 12 divided government states.