Stirewaltisms: It’s Time for an Age Limit for Federal Office

IT’S TIME FOR AN AGE LIMIT FOR FEDERAL OFFICE

The constitutional age requirements for federal office—35 for president, 30 for senators, 25 for representatives—make sense. But they aren’t enough.

As Americans, especially elites, live longer and longer, we need upper limits, too. Not only are there considerations about the abilities of individual office holders, but about having a government that reflects the nation as a whole. I suggest a maximum age of 79 for all federal offices, including the Supreme Court. I’m certainly open to different ages, but let’s start there.

This is not primarily about the current president, his predecessor (both of whom would be disqualified in 2024 under my proposal) or the current members of Congress and the court. Partisans, supporters, and detractors could make all kinds of arguments about why certain very old people are good or bad at their jobs. What I am worried about is gerontocracy. The Founders’ generation did not know that most Americans would one day not only live so long or that they would remain so active into their later years.

The Constitution sets minimum ages for offices to make sure that the members of the government have enough maturity and practical experience to be effective in office and be good stewards of power. Youthful inexperience and excessive exuberance is still a problem today for sure. Teenagers don’t vote in large enough numbers to usually make a great deal of difference, but I can certainly see the argument for restoring the 21-year-old voting age. Based on what we know about the development of the human brain even since the age was lowered 50 years ago, 18 certainly seems young for full majority status.

But the Founders didn’t need to worry about the upper limits of age because nature mostly took care of that for them.

In 1820, the first Census to yield useful numbers on the ages of Americans, the median age was 16.7 years. It is now 38.1 years. The shift is partly because people live longer now than before, but also because we were a younger nation in every sense of the word. People had a lot more kids and started having them at much younger ages. Forty-year-old grandmothers were not rarities 200 years ago. Forty-year-old new mothers are not rarities now.

A great deal of todays’ life expectancy is, of course, thanks to advances in eradicating childhood disease and decreases in deaths related to childbirth. This explains a lot about why the estimated life expectancy for residents of select Massachusetts towns in 1789 was 36.5 years while American life expectancy is now 78.8 years. But we do not really care about life expectancy at birth for the sake of federal offices. We care first about how the people of the Founders’ generation thought about age.

There’s evidence to suggest that for their peers, the life expectancy for mature men—those of similar status who had reached the age of 15—was 62.8 years. That’s 16 years shorter than the American male life expectancy from birth today. The average age of the delegates to the convention that produced the Constitution and its age requirements was 42. The median age in the current Senate is 64.8, in the House, it’s 58.9. While modern congressional averages are probably helped by the inclusion of women starting in 1917 and their longer average life spans, the increase from the median age of the delegates to the Constitutional Convention to the members of the House, 16.9 years, is almost identical to the shift in the male population overall.

What if the trend continues? There’s no guarantee that it will, and the passing of the baby boom generation and the size of the millennial cohort will probably produce a temporary decrease in median ages of politicians and the public. But what if, over the long haul, life expectancies continue to rise, especially for elites, and the ages of our leaders rise along with them? Incumbency is very powerful, so once a member gets a seat he or she may remain there for decades. It’s also increasingly hard to do anything but serve in Congress after one gets elected, another barrier to entry for younger Americans.

The continual campaign cycle and stricter limits on outside income means the old concept of citizen lawmakers is harder to keep up. That pushes ages up, too. Normal considerations of people in their prime years—raising families and making money—are harder for lawmakers today even compared to very recent history. House members today make $174,000. That’s a lot if you live in Slab Fork or Dilles Bottom, and would be comfortably upper middle class in most of the country. But if you need to rent a place in Washington, that takes a bite. The inflation-adjusted pay of members in 2000 was equivalent to about $250,000 today, so in real terms, pay is going down. Ethics rules cap earnings from other work at about $28,000, so a second job can’t make up the difference, even if you had the time.

I’m not calling for a congressional raise, though I can see the need for one. I am, however, pointing out that for exceptional women and men in prime earnings years, Congress represents not just a pay cut, but a loss of crucial earnings years. It stands to reason then, that you will get fewer exceptional young members and lots more members who are old enough to not worry about such things. That would be the case even if we enacted term limits, as I now believe is also necessary. A full-time Congress with relatively modest pay is yet another advantage for the over-60 set.

Then there are the voters. We know older Americans are much more likely to cast ballots than their younger counterparts. But it’s probably even steeper than you think. In 2020, voter turnout was highest among Americans ages 65 to 74 (76 percent). The lowest turnout group, those ages 18 to 24, was just 51 percent. If senior citizens are 50 percent more likely to vote than young adults, what we know about implicit bias tells us that there will be a strong baseline preference in the electorate for older candidates.

I tend to think that, beyond the extremes, there’s probably a pretty low correlation between age and excellence in leadership. Young members aren’t better than old members. Justices in their 70s don’t necessarily have more wisdom than those in their 50s. You can be a bad president at 35 just as easily as you can at 80. That’s different, however, than saying age doesn’t affect competency on the whole.

And then there’s the big problem. Even the most robust, brilliant 85-year-old sees the world differently than the people who are in the middle of life. It’s important that the voices of the people with the most skin in the game—those raising families, in their prime working years—have a strong voice in the setting of national policy.

Less than a quarter of the signatories of the Declaration of Independence were older than 50. Just four of the 54 were over 60, and only one, the great Ben Franklin, was 70. Thirty-two members of the current Senate are older than 70. Six are over 80. Chuck Grassley of Iowa, now seeking an eighth six-year term, was born during Franklin Roosevelt’s first year as president. Even considering the shorter life expectancies of the Founders’ era, our leadership is very old by historical standards.

America needs more young leaders. But if places for them to arise are disproportionately filled by octogenarians and, maybe one day soon, nonagenarians who enjoy substantial competitive benefits over younger office seekers, we will miss out. A constitutional amendment capping the age for federal office at 79 would help shift the balance.

There are lots of things that might help to reform the federal government, like expanding the number of seats in the House, term limits, repealing the 17th Amendment, member dormitories and many more. But age limits should certainly be included on the list.

Holy croakano! We welcome your feedback, so please email us with your tips, corrections, reactions, amplifications, etc. at STIREWALTISMS@THEDISPATCH.COM. If you’d like to be considered for publication, please include your real name and hometown. If you don’t want your comments to be made public, please specify.

STATSHOT

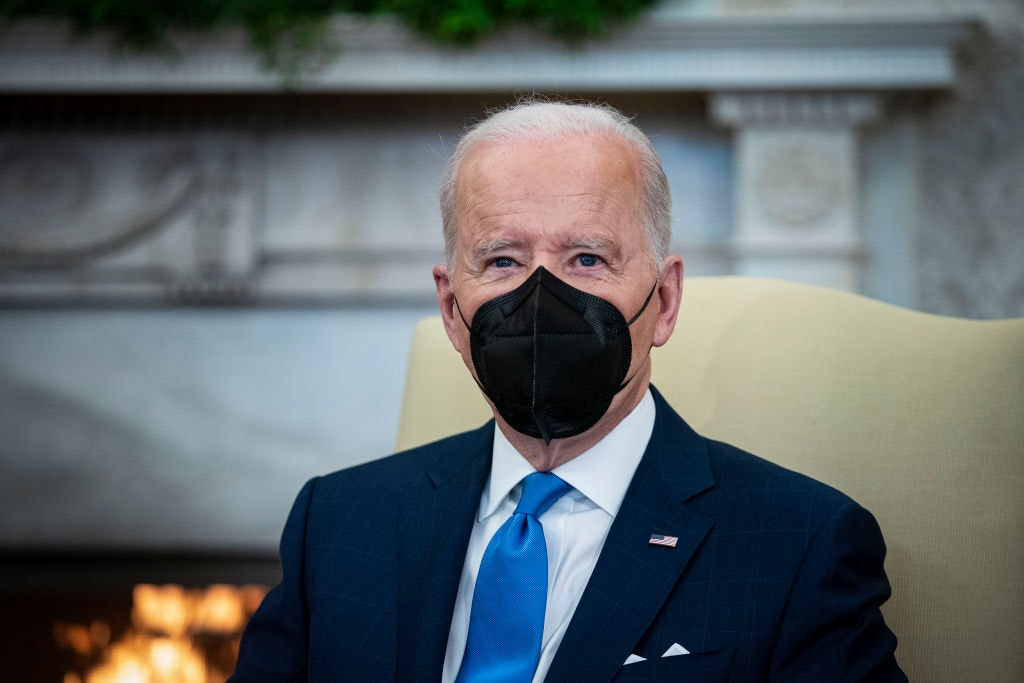

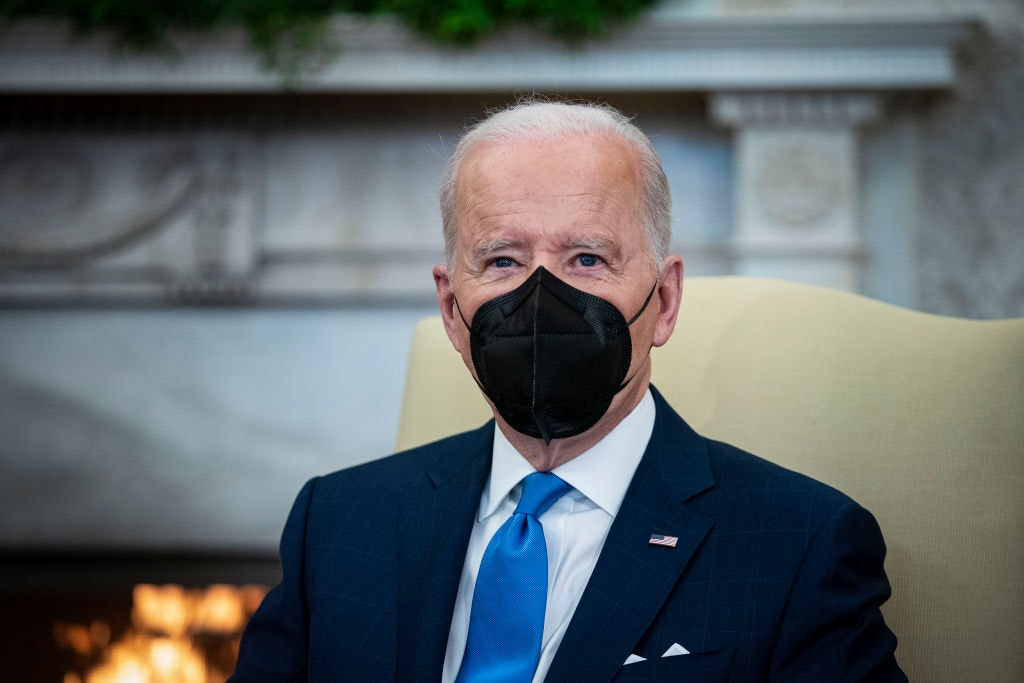

Biden job performance

Average approval: 42.8 percent

Average disapproval: 53.6 percent

Net Score: -10.8 points

Change from one week ago: ↓ 0.8 points

[Average includes: Ipsos/Reuters: 44% approve-51% disapprove; Ipsos: 43% approve-53% disapprove; CNN/SSRS: 41% approve-58% disapprove; Ipsos: 41% approve-56% disapprove; Ipsos: 45% approve-50% disapprove.]

Generic congressional ballot

Democrats: 43.8 percent

Republicans: 45.8 percent

Net advantage: Republicans +2 points

Change from one week ago: Republicans +0.6 points

[Average includes: CNN/SRRS: 43% Democrat, 44% Republican; Monmouth University: 43% Democrat, 51% Republican; Fox News: 43% Democrat, 44% Republican; NBC News: 47% Democrat, 46% Republican; Quinnipiac University: 43% Democrat, 44% Republican.]

TIME OUT: AN APPLE A DAY

The Atlantic: “Starting in the late 20th century, medical groups asserted that America had an oversupply of physicians. In response, medical schools restricted class sizes. From 1980 to 2005, the U.S. added 60 million people, but the number of medical-school matriculants basically flatlined. Seventeen years later, we are still digging out from under that moratorium. … The U.S. is one of the only developed countries to force aspiring doctors to earn a four-year bachelor’s degree and then go to medical school for another four years. (Most European countries have one continuous six-year program.) Then come the years of residency training. … Doctor burnout and brutal 16-hour shifts for residents and M.D.s aren’t necessary tests of willpower; they’re just the inevitable result of not having enough people to do the work that today’s hospitals demand. … If COVID continues to be a problem for the U.S.—and that seems likely—we’re going to need more physicians, clinics, and therapies. Even if COVID disappears and the U.S. never faces another pandemic ever again … we’ll be an older and aging country with more sick people. … No matter what the pandemic future holds, we need more doctors to be part of America’s health-care system.”

DEM RESEARCH: GOP CULTURE ATTACKS ‘ALARMINGLY POTENT’

Politico: “Democrats’ own research shows that some battleground voters think the party is ‘preachy,’ ‘judgmental’ and ‘focused on culture wars,’ according to documents obtained by [Politico]. And the party’s House campaign arm had a stark warning for Democrats: Unless they more forcefully confront the GOP’s ‘alarmingly potent’ culture war attacks, from critical race theory to defunding the police, they risk losing significant ground to Republicans in the midterms. The Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee is recommending a new strategy to endangered members and their teams, hoping to blunt the kinds of GOP attacks that nearly erased their majority last election and remain a huge risk ahead of November. In presentations over the past two weeks, party officials and operatives used polling and focus group findings to argue Democrats can’t simply ignore the attacks, particularly when they’re playing at a disadvantage. A generic ballot of swing districts from late January showed Democrats trailing Republicans by 4 points, according to the polling.”

McConnell digs in: New York Times: “As [Former President Donald Trump] works to retain his hold on the Republican Party, elevating a slate of friendly candidates in midterm elections, [Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell] and his allies are quietly, desperately maneuvering to try to thwart him. The loose alliance, which was once thought of as the G.O.P. establishment, for months has been engaged in a high-stakes candidate recruitment campaign, full of phone calls, meetings, polling memos and promises of millions of dollars. It’s all aimed at recapturing the Senate majority, but the election also represents what could be Republicans’ last chance to reverse the spread of Trumpism before it fully consumes their party. …the message that he delivers privately now is unsparing, if debatable: Mr. Trump is losing political altitude and need not be feared in a primary … Mr. McConnell is blunt about the damage he believes Mr. Trump has done to the G.O.P., according to those who have spoken to him. Privately, he has declared he won’t let unelectable ‘goofballs’ win Republican primaries.”

Women lead the way as GOP targets Hispanic Texans: Politico: “Democrats were caught off guard by Donald Trump’s numbers in South Texas in 2020. The Hispanic Republican women who live there were not. Many of them have played a leading role in urging their neighbors in majority-Hispanic South Texas to question their traditional loyalty to the Democratic Party. Hispanic women now serve as party chairs in the state’s four southernmost border counties, spanning a distance from Brownsville almost to Laredo — places where Trump made some of his biggest inroads with Latino voters. A half-dozen of them are running for Congress across the state’s four House districts that border Mexico, including Monica De La Cruz, the GOP front-runner in one of Texas’ most competitive seats in the Rio Grande Valley. … They want more border security or are staunchly against abortions. … They worry Democrats are hostile to the oil and gas industry, which provides many good-paying jobs in the state.”

RIP P.J.

I have been delighted to see the many loving tributes to P.J. O’Rourke, who died Tuesday at age 74. He was so kind and gracious to me on the occasions when our paths crossed that I have always kept a special place in my heart for him. It’s been great to see his wit and iconoclasm on display, but my favorites of his work was the gonzo stuff he did for Rolling Stone in the 1980s. He was a helluva good reporter. In 1986, he went to the Philippines to cover the historic election in which Cory Aquino was taking on the corrupt U.S.-backed President Ferdinand Marco. O’Rourke’s piece on the U.S. senators who claimed they came in the name of freedom was dynamite.

“Most of the Potomac Parakeets were a big disappointment. Massachusetts Senator John Kerry was a founding member of the Vietnam Veterans Against the War, but he was a bath toy in this fray. … I can tell you what any red-blooded representative of the U.S. Government should have done. He should have shouted, ‘If you’re frightened for your safety, I’ll take you to the American embassy, and damn the man who tries to stop me.’ But all Kerry did was walk around like a male model in a concerned and thoughtful pose.”

Chef’s kiss… Rolling Stone has a paywalled archive, but I encourage anyone to get ahold of his book, Republican Party Reptile, that includes this and other gems.

BRIEFLY

Houses on streets with Confederate names fetch lower prices—Bloomberg

Citadel CEO donates $20 million to Aurora mayor Richard Irvin for Illinois gubernatorial GOP primary—Chicago Sun-Times

Enviros have beef with Biden for letting up on livestock amid high meat prices—Wall Street Journal

WITHIN EARSHOT: HONESTLY…

“This is what happens when you try to rename the schools in the middle of a pandemic! We wanted to show the diversity of the community behind this recall. I knew they were going to say, ‘Oh isn’t it just a bunch of Republicans?’ and I’m like, do I look like a Republican?” — David Thompson a.k.a “Gaybraham Lincoln”, a San Francisco United School District parent dressed in head-to-toe rainbow drag and towering platform shoes at a rally for recalling three San Francisco school board members who pushed through a controversial plan to rename a third of the district’s schools, including one named for Abraham Lincoln, even as the board could not get students back in class during the pandemic.

MAILBAG

“Thanks for the concise argument (as always) about the Covid “issue.” It’s been exhausting living inside the beltway throughout all of this, but especially in the last several weeks, I’ve been grappling with the lack of admission that the issue is done, but not been able to put my thoughts into words. As stated above, it’s no surprise that Chris makes a clear and concise case on this issue, but this one really had me befuddled for some reason (this extravert that lives alone has struggled to maintain perspective in so much remote work), so I appreciate it greatly!!”—Abbey Hagar, Alexandria, Virginia

Thank you, Ms. Hagar! Your experiences in Alexandria have probably been very different from Americans in a lot of places. One of the things I love about traveling for my work has been getting to see what “normal” looks like around the country. In some places, like Alexandria, there’s still a lot of signs of the pandemic, but they are receding. New York, on the other hand, still felt very much like it was in the throes when I was just there. In Central Illinois, where I was this week, you could only find COVID precautions at national chain outlets or federally regulated places, like the airport. The people in each of those places had widely divergent collective experiences with the virus, are demographically very different from each other and have dissimilar politics. One of the problems with the CDC is that it can only have one set of guidelines which can’t really take those things into account.

“I’d like to make a distinction you might agree with but I’m not sure I saw represented in your newsletter today, Democrats Have Issues About COVID Restrictions. Call me a knuckle dragger, but from almost the moment this whole disaster began I was 100% against masks and all the other restrictions and rules OUTSIDE of medical settings. I’m not a monster after all. I read Dr. John Ioannidis from Stanford in the WSJ back then and thought, “Yep, he gets it.” Then our long descent into madness began. I’m 100% in favor of vaccines—if you want them. 100% in favor of going anywhere and doing anything you want. I’m 100% in favor of you wearing a mask. 100% in favor of protecting the truly vulnerable. I’m 100% against masking children. And I’ve held those positions without wavering since March of 2020. And I’m not alone. I have many friends who feel the same way. And many who don’t, too. But my point is that your piece seems to define two extremes when there’s always been a robust middle ground (where I see myself) that doesn’t get a voice. Masks are and always have been a joke. And that’s from multiple doctor friends here in Nashville and Franklin TN. Unless you have an uncomfortable and perfectly fitted N95, it’s theater. Even for an innumerate idiot like me, following the CDC weekly updates and looking at the tables is pretty simple. We knew who was dying and why almost from month one. And it wasn’t people like me. Not even close. Yes, there are the crazy liberal jackasses and the crazy conservative jackasses. But there’s also a sizable group who were right from the beginning and just wanted common sense applied.”—Todd Lemmon, Brentwood, Tennessee

I think it’s important to remember, Mr. Lemmon, that “middle ground” is in the eye of the beholder. Humans tend to imagine that we are in the sensible space on the spectrum. Yes, we all have views that we know may sound extreme to others or be out of step with the mainstream. For example, my white-hot intolerances for the designated hitter rule, the primary election system, and the worship of Theodore Roosevelt are beyond normal. I’m okay with that. But on the most public policy questions, I flatter myself to think that I am in the sensible space of “normal.” But we can’t all be “normal” and have as many profound disagreements as we do. This is why it is important to avoid strong opinions unless absolutely necessary. As I am overly fond of saying, opinions are luxury items, don’t have more than you can afford. While you may feel that you have been right all along on the question of COVID restrictions, I would encourage you to find some grace for the people who you think have been wrong. The problems were bewildering at the outset and many of the best and brightest have managed to be wrong multiple times and in multiple directions. While I am sure that there have been people in positions of power who have been intoxicated by the enhanced authority that came with health restrictions, I believe most folks were doing what they thought was right. And I feel the same about msst of the folks who have opposed restrictions. I don’t think they wanted to hurt people or prolong the pandemic, I think that they saw the situation differently. That’s why we need to show each other what Peggy Noonan calls “patriotic grace.” If we remember that the people with whom we disagree probably also think that they are part of the “robust middle ground” you describe, it’s easier to see them as our fellow flawed humans, not enemies. We owe each other room to be wrong sometimes because we will be wrong ourselves.

“You imply that masks are no longer necessary in schools because we have vaccines. Yet, many parents have yet to allow their children to be vaccinated. This means that the value of vaccines for school aged children is not yet fully realized. This makes it doubly hard on teachers and on people who would like to have the mask mandates removed due to the vaccine efficacy. I don’t like wearing a mask, but will continue to do so as long as there are significant numbers of people who refuse to be vaccinated (in addition to the ones who cannot be vaccinated due to health conditions), and as long as there are still thousands of people being infected each day and large numbers of people dying from this virus every day, primarily though not exclusively, through contact with unvaccinated persons. When the numbers drop down below the number of people who die from flu each year, I may consider that we have reached a point at which the benefits of wearing a mask are outweighed by the negatives. I will continue to get the vaccines as needed, just as I do for flu, and admit then to the freedom of others to choose to take the risk of not doing so for themselves. At the moment, though, they are not just taking the risk for themselves and their children, but for other people— vulnerable and healthy ones. You may feel otherwise, but I do not consider this a hard line approach. I would agree that part of the problem of addressing this and other issues is that each person believes he or she is taking a principled stand. My principle is the necessity of an individual and the community together to look out for the health and welfare of the community as a whole and especially for the most vulnerable in the community. I understand that people who feel very differently are just as convinced that their principle of individual freedom, especially freedom from governmental overreach, is paramount. Entrenched as we are in our personal perspectives and principles, it is difficult to find ways to work together. Yet for the good of the community, and thereby also for the good of individuals within the community, we need to be able to do so. Perhaps it would help if more people sought to find the principles we have in common rather than the ones that divide us. Thank you for your thoughts, and for listening to mine.”—Merritt Schatz, Oxford, Pennsylvania

Thank you for your lovely, thoughtful response! First and foremost, I was offering political observations on why this is such a hard corner for Democrats to get out of. Politics, though, is not real life. Very often the most politically expedient thing to do is in fact the wrong thing. There is a low correlation between virtue and popularity, as any glance at mainstream cultural offerings will rapidly confirm. People have to do what they think is right for themselves, the people they love and their neighbors. That should always trump narrow partisan interest. As soon as I read your words, “Perhaps it would help if more people sought to find the principles we have in common rather than the ones that divide us,” I repeated them as a prayer. It is what America so badly needs right now.

“Without conducting a full inventory, I suspect that most of the columns I read where the author responds to questions sent in by readers follow a convention of running the questions in italics and the author’s answer in standard text. Do any other readers find your layout goes against the grain?”—Michael Garrett, Montclair, New Jersey

Just this once for you, Mr. Garrett.

“My sense is the vast majority of American voters would select others or someone else if they could in some Presidential matches given the dearth of quality leaders. The two parties put all of us in the situation of having to choose the lesser of two evils. A Hillary Trump rematch or a Biden Trump rematch might make the entire country revolt or collectively throw up. Should I really believe the polls vis a vis how the GOP feels about Trump? My sense is that while many agreed with Trump on some of his policies I cannot believe that a majority of GOP voters want that chaos again. It also seems that Trump’s hold on the party is loosening….Ronna McDaniel notwithstanding. I do fear that having 13 candidates would allow Trump to get more votes than some backbencher wannabe President.” — Earl King, Colts Neck, New Jersey

Certainly that’s the house line in the political analysis casino, Mr. King. For me, though, we’re still 265 days from any really intelligent analysis of how things will shape up. Parties tend to think about the previous election rather than the next one. Democrats nominated the guy in 2020 whom they should have nominated in 2016, for instance. Trump benefited from an oversized, overfunded, but still underwhelming primary field in 2016. It’s reasonable for Republicans to worry that the same thing will happen again. Renominating Trump is the single most obvious blunder the party could commit, but sometimes parties commit blunders everyone sees coming—like Democrats did in 2016. But it won’t be until the day after the midterm elections in November that we will really get a sense of how the Republican primary electorate will be thinking. Nothing has been as bad for Trump’s chances as Glenn Youngkin’s victory in Virginia, which was proof of concept for the idea that Republicans need Trump mostly out of the picture to win in the suburbs. How the midterms go will set expectations among the members of the GOP. Do nationalists sweep the primaries and then lead the way in retaking both houses of Congress? If so, Republicans will be much more likely to buy their tickets to MAGA III: The Revenge, but the field will also be less crowded since potential candidates themselves may conclude that there’s no point. That may be a good thing or a bad thing for the GOP, depending on the quality of the candidates and how well Trump is keeping it together. Is it conservatives and moderates leading the way in 2022? The field probably gets more crowded as Trump-phobic candidates develop new courage. If Nikki Haley and the rest of the finger-in-the-wind crowd all gets in, you could certainly see a repeat of 2016. But in that case, the 2022 results would also speak to changing attitudes in the Republican electorate. And don’t forget the other big force driving the shape and size of the Republican field: Republican perceptions of the likelihood of victory in the 2024 general election. How valuable will the Republican nomination appear to be? That’s a very long way of saying, it’s too soon to worry much about it. Half of the stuff people are wearing themselves out over now will be moot by Christmas.

You should email us! Write to STIREWALTISMS@THEDISPATCH.COM with your tips, kudos, criticisms, insights, rediscovered words, wonderful names, recipes and always good jokes. Please include your real name—at least first and last—and hometown. Make sure to let me know in the email if you want to keep your submission anonymous. My colleague, the ever-resourceful Samantha Goldstein, and I will look for your emails and then share the most interesting ones and my responses here. Clickety clack!

CUTLINE CONTEST: THE WEIRDING WAY

Last week’s cutline contest submissions from Groundhog’s Day were pretty hard to top. But just in time for the D.C. mask mandate repeal, here’s the winner for this week:

“Duke Joseph Atradies Biden surveys the new cabinet on Arrakis before taking off his still suit mask.”—Rehm Maham, Austin, Texas

Honorable mention:

“Bane is ANGRY that they ran out of lime jello at the Legion of Doom senior center.”—Will Miller, Denver, Colorado

Submit your own! Readers should send in their proposed cutline for the picture that appears at the top of this newsletter to STIREWALTISMS@THEDISPATCH.COM. We will pick the top entrants and an appropriate reward for the best of each month—even beyond the glory and adulation that will surely follow. Be hilarious, don’t be too dirty, and never be cruel. Include your full name and hometown. Have fun!

KICKER: THEIR EYES WERE WATCHING PUTIN

AP: “ A Russian gallery says one of its security guards has vandalized an avant-garde painting on loan from the country’s top art repository by drawing eyes on the picture’s deliberately featureless faces. It said the damage can be repaired. The Yeltsin Center in Ekaterinburg said the vandalism of the painting “Three Figures” by Anna Leporskaya occurred Dec. 7. It said the suspected culprit worked for a private company providing security at the gallery. The painting, dating from the 1930s, shows three torsos and heads with hair but no facial features; the vandal drew eyes on two of them with a ballpoint pen. The Yeltsin Center said the painting has been sent for restoration to the State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, which owns it.”

Chris Stirewalt is a contributing editor at The Dispatch, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and the author of Broken News, a book on media and politics due out in August. Samantha Goldstein contributed to this report.